Why Use These Theories?

My object of research, the academic interview, exists within

the at least partially definable ecological space of academia. For this reason, theories that hold

ecological views about social action are likely to be relevant. Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT)

and its predecessor, activity theory (AT), are two reasonable choices. Arguably, actor-network theory would also be

a valid candidate, but a secondary motivation for me in choosing the activity

systems theories is to examine how the first generation theory, AT, compares

with its more elaborated version, CHAT.

The fact that both are still used as theoretical frameworks makes it

reasonable to examine them side-by-side even though, in fact, CHAT evolved from

AT. I am also interested in examining

Paul Prior and his fellow authors’ (2007) attempt to adapt CHAT as rhetorical

theory. Because Prior et al’s version

turns out to be something of a Franken-theory with elements that are

challenging to translate into an analysis, I will not apply it. However, I will make a few comments on it at

various points.

About the OoS

The

published academic interview, my object of research, can be found in a number

of places. The most obvious is in

academic journals. A recent search, for

example, quickly turned up two 1995

interviews of Charles Bazerman, one in

Composition

Studies (Crawford, Smout, & Bazerman) and one in

Writing on the Edge (Eldred & Bazerman). Interviews also receive book-length

treatments. An example is

Conversations with Anthony Giddens, composed

of seven thematic interviews with the prominent sociologist (Giddens &

Pierson, 1998). Another is

An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology,

which is described as “Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘discourse on method’” (Bourdieu &

Wacquant, 1992, back cover) but has as its second and longest section an

interview of Bourdieu by Wacquant. Finally, it is possible to find academic

interviews that are primarily distributed online. Online journals can include interviews, such

as McNely’s (2013) interview of Spinuzzi as described in my first case study. It

is also possible to find interviews online that are transcriptions of oral

interviews, such as, for example, the 18

visiting speaker interviews included

in Florida State’s Rhetoric and Composition department site.

In spite of the fact that, as we

can see, the interview is a robust form that is published in different media

and is distributed in several ways, very little research has targeted this

genre. One of the few is Arnold’s (2012) look at Michel Foucault’s interviews

as a particular genre within his larger body of work. Although Arnold doesn’t examine the academic

interview as a genre, she does examine the ways that Foucault used the

interview as a space to make theoretical statements that transcended his

specific published works. Another look

at a specific scholar’s interviews is Chakraborty’s (2010) discussion of how

Gayatri Spivak’s interviews brought together “the scholarship with the persona”

(p. 623). Chakraborty also examines the way that such interviews allow public

intellectuals to “use the interview as a modus vivendi to produce intimate interlocution

with their chosen constituency” (p. 627). In both Arnold’s and Chakraborty’s

discussions, however, the focus is primarily on the scholars rather than the

genre. In terms of looking at how genres

are situated, Tachino’s (2012) study of intermediary genres might serve as a

model. Though Tachino is looking at a completely different activity system,

namely the judicial system, the concept of “a genre that facilitates the ‘uptake’

of a genre by another genre” (p. 455), almost certainly applies in the case of

the academic interview. One outcome of

an academic interview is almost certainly increased uptake of a scholar’s

published works. A similar case is the

use of published interviews as a mediating genre for avant-garde artists to

discuss their art, as discussed by Bury & Scott (2000).

Mediation: A Core Concept

The idea of an intermediary genre

leads us to the idea of mediation, a concept at the core of both activity theories,

AT and CHAT. As Russell (1995) notes, activity

theory owes a significant debt to Russian psychologist Vygotsky. Vygotsky emphasized that “the structure and

the meaning of the tool in a community… strongly influence the actions that people

accomplish, and as such the cultural tool is a strong semiotic component of the

learning process” (van Oers, 2010, p. 8). Since Vygotsky’s theories were connected to

learning, unsurprisingly they have frequently been used by educational

theorists. However, because “activity

theory analyzes human behavior and consciousness in terms of activity systems,”

or in other words, “goal-directed, historically situated, cooperative human interactions”

(Russell, 1995, p. 53), it is obvious that these theories can be applied to many

settings. For example, activity theory

(AT) has been employed by at least two writing scholars Russell (1995) and

Nowacek (2011). Both use the “mediated

action triangle” that Yamagata-Lynch (2010) identifies with first generation

activity theory. However, Yamagata-Lynch

points out that “many CHAT scholars now encourage investigators to engage in

new work within an interventionist framework using third generation activity

theory” (p. 23). This version correlates

with the framework that Spinuzzi applies in his 2003 study. The idea of mediating artifacts continues as

a Vygotskyan core concept that remains at the heart of both versions.

When applied to my object of study,

the interview genre fits slot of “tool” or “mediational means” in activity

theory and of “instrument” in cultural-historical theory. In other words, it is

posited as a core node in each case.

Incidentally, the central role of a mediating tool or artifact is

obscured in Prior et al’s theory of CHAT because mediators are not nodes in this

version. In fact, the authors discuss

mediation as a concept but do not include it explicitly in the conceptualization,

“Remapping Rhetorical Activity: Take 2.”

Instead, they argue, “We take mediated activity and mediated agency as

fundamental units of analysis. In those terms, everything in the three maps

(literate activity, functional systems, and chronotopes) is about mediation”

(p. 22). Clearly, this

mediation-is-everywhere stance is a significant departure from the more focused

version of AT/CHAT. To be honest, many terms

in their list, such as communities, ecologies,

activity, and socialization, are

so general that it is hard to imagine the idea of mediation having the

theoretical potency that it has when it is associated with a tool or

instrument. While it is true that in a

sense, these abstract categories are mediating, in another way, the conceptualization

moves mediation from node to connecting channel. This idea of connections as inherently

mediating draws Prior et al’s version of CHAT closer to actor-network theory. At the same time, the theory lacks the

precision of ANT because Latour (2005) insists on careful tracing and labeling

of connections. To see abstract categories as mediating seems to fall into the

everything-is-social pit that Latour labors so hard to banish.

How the Network is Structured

The network formulation associated

with AT and CHAT, i.e. the nodes, structuring of nodes, agencies and

relationships within and between nodes, is where the first generation theory

(AT) diverges from the more elaborated version (CHAT). I will take each in turn. Activity theory is

usually represented by a triangle with the “mediational means” at the top, the

“subject” on the left, and the “object” or “objective” on the right. An additional arrow emerges from the corner

of the triangle pointing towards “outcome(s),” meaning that human agents use

mediational means to work towards goals in the activity system, and this should

generate hoped-for outcomes. There are a

couple of implications here. First, it

is the human agents who have agency.

Tools are used intentionally by these agents to work towards conscious

results. Other objects and proximate

groups have little relevance within this model. However, subjects, tools, and

objectives are assembled together in the drive towards outcomes.

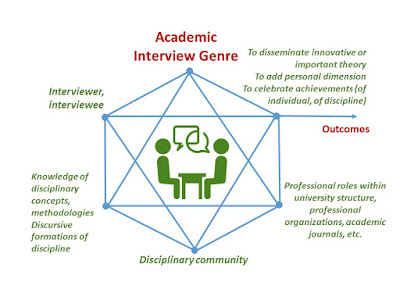

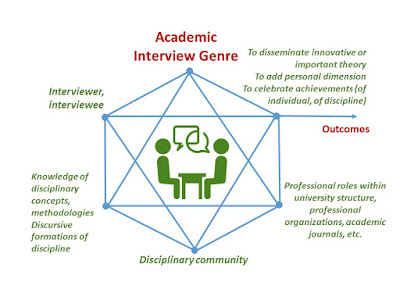

Since in my application of the

theory the academic interview is the mediational means, or tool, as we have

said, the interviewer and interviewee work together constitute the subject, the

agents who work together to accomplish a goal of illuminating a scholar’s

ideas, motivations, influences, personal idiosyncrasies and other interview

content. The hoped-for outcome, one imagines, would be

the increased circulation of the scholar’s ideas within the disciplinary

community. Of course, there may be

supplementary outcomes, such as reinforcing the values of a discipline,

educating interested parties outside the discipline, mentoring disciplinary

novices, and so forth.

Although Spinuzzi (2003) describes

his framework as “activity theory” (p. 36), the diagram on page 37 demonstrates

that his version bears a great resemblance to what is usually described as cultural-historical activity theory, or

CHAT. In an important expansion of

activity theory, Engeström (1987), one of the theory’s main proponents, added

an additional row to the bottom of the original triangle to draw in more of the

ecological context of the activity system.

This is what is now typically known as CHAT. The first additional node is rules, followed by community, and finally, division

of labor. These are stretched out to

make up the bottom row of a larger triangle, with lines drawn between each

point. Spinuzzi’s version has two minor substitutions,

namely, to replace subject with collaborators,

and rules with domain knowledge. However, the appearance of the diagram is

altered. Instead of embedded triangles,

each node is pulled out to constitute vertices in a hexagon. Since both diagrams connect the points to

multiple other points, the result is not fundamentally different, but it does

suggest that Spinuzzi wants points to be visually and logically equivalent. This contrasts with Engeström’s

version where the arrangement might imply that in some way the subject is

caught between rules and mediating tools, for example.

To apply the model to academic

interviews, we add to the previously-mentioned tools, subject, and object, the

domain knowledge of the discipline within which the interview takes place,

which is normally also the discipline of the scholar being interviewed. The content knowledge and research objects of

the discipline would be included here as well as, arguably, the discursive

formulations of the discipline in a Foucauldian sense, that is, what can be

talked about and how. The community

clearly would be the disciplinary practitioners and other scholars working

within the discipline. The division of

labor can capture the point that one “collaborator,” to use Spinuzzi’s term, is

the scholar being interviewed and the other is the interviewer, usually

another, less established scholar in the discipline, who, although named, is

nevertheless rendered less visible in the greater light of the luminary being

interviewed. Perhaps, too, we can extend

the division of labor to include other actors in the publication process, such

as journal editors, archivists and webmasters and so on. If this is the structure of the network, we

can see that agency has now been dispersed since collaborators and community

both involve human agency. Of course not

all human actors have the same level of agency; the community arguably has less

impact on the activity system than the collaborators per se.

In an important sense, CHAT can capture more of the ecological

framework that makes up the activity system.

After all, when we analyze the interview genre within the activity

system, we should recognize that the system entails more than just scholars

talking to other scholars. In a way, the

entire institution of the university is activated with all its moving parts,

from financial aid to student support services to plant services. Scholarship depends on the educational

enterprise that defines the scholar as professor and enables the scholar as thinker. The educational enterprise in turn depends on

a complex of supporting staff, facilities and equipment. The interview captures the professor as

scholar. Although the professor also writes

in an array of other genres: exams, syllabi, annotations on student papers,

emails, proposals, catalog descriptions, textbook adoption forms, expense

reports, and others, the interviewer does not ask the interviewee to comment on

these. The genres that are most highly valued

and frequently discussed are research articles and books. The interview may, however, mention

dissertations and conference presentations as well as genres of public

engagement such as blogs, TV interviews, newspaper columns, etc. By calling the larger ecology into play, CHAT

allows us to recall these other professional activities, whereas activity

theory’s first generation model largely narrows the focus to the interview itself

with a nod to the larger, though unelaborated, activity system.

Although in one way Prior et al’s

version of CHAT offers an even more powerful model than the two versions

mentioned so far, it also has some significant disadvantages. The “functional systems” part of the model

overlaps to a degree with CHAT, as it includes people, artifacts, practices, institutions, communities, and ecologies. In addition, the “literate activity” list,

includes production, representation,

distribution, reception, socialization, activity, and ecology. The purpose of the “literate

activity” list is to replace the five terms of the classical canons of rhetoric

with a more effective model. This is a

laudable goal that certainly extends the reach of the theory. The disadvantage is that it is hard to see

where literate activity fits into the larger model. If we were to adapt Spinuzzi’s diagram, for

example, where would the literate activity fit?

In the middle of the hexagon?

Should it be seen as an elaboration of activity in which each step

activates all parts of the hexagon? To

complicate matters, we have the concept of the “laminated chronotopes,” a term

that is not well-defined in the article.

Chronotopes are introduced as being “in the broadest context” and at the

same time, “embedded in semiotic artifacts” (p. 19). Does this perhaps mean that the application

of the theory is like the embedded Russian dolls where the artifact examined has

nested within it the whole universe of the activity system that created it,

within which is another artifact with its

activity system inside and so on down the line?

The biggest problem for me, however, is the “functional systems” list

which replaces Spinnuzi’s hexagon or Engeström’s embedded triangles with a

loose list of items that are not defined in the article. Prior et al claim that the “CHAT map points

to a complex set of interlocking systems within which rhetors are formed, act,

and navigate” (p. 22). While complex interlocking

systems and a “perspective that integrates communication, learning, and social

formation… as simultaneous, constant dimensions of any moment in life” (p. 23) are

intriguing, they may make the model too complex and too comprehensive to be meaningfully

applied to any single research project.

Movement and Change

To return to network structures

that we have established for AT and CHAT, we need to consider the network as a

dynamic system. What moves? How does it move? How does the dynamic nature

of the network allow the network to change or evolve? Within the AT triangle, as already stated,

there is a forward trajectory where the elements of the activity

system—subjects using tools to accomplish objectives—work together to move

towards outcomes. Considering that we

are applying the model to a genre of writing, the action here is rhetorical

action. What is moving through the

network is the actions taken in time to accomplish the goal and reach the

outcomes. As in a physical system, there

are forces driving results. The best candidate for these forces is the agency

of the subjects employing the genre as a tool.

Since we have already established that the basic system of AT remains

within CHAT, this dynamic also applies to the CHAT network. The difference is that the actions that move

through the system, the forces of agency, now have more internal structure,

since the knowledge or rules that apply, the larger community that may

influence the actors (“collaborators”, again to use Spinuzzi’s term), and the

structural system within the community or organization that does the acting

(“division of labor”) all leave their traces on the packaging of the action as

it moves forward. It is easy to see how

these elements shape the academic interview.

At times, as when an interviewee mentions scholarly influences or describes

the development of ideas within a discipline, these elements may emerge within

the text of the interview. In both

activity theory models, I see the network as operating like a machine that is

activated to package and produce a rhetorical artifact or event. If we persist in seeing the genre as the tool

or mediational means, then we may see the text as the distributional outcome of

the work of the network. In this

conceptualization, the content or the meaning comes to exist when it is package

and moves forward as a stable artifact.

What happens as the text emerges from the activity system, as it moves

into “outcomes,” is less certain.

Presumably it enters a new activity system to enter the community and be

taken up as domain knowledge, or even, depending on its content, to argue into place

new instruments, changes to community, adjustments to divisions of labor and so

forth. If this understanding is correct,

we have to assume that the activity system lies within a larger universe of

activity systems. Perhaps this is what

Prior et al are trying to achieve with the separation of ecology (the single activity system that packages a given text?)

and ecologies (an interlocking

network of activity systems?) Incidentally,

Prior et al suggest that what travels through the network is not only action,

but cognition. “Mediated activity means

that action and cognition are distributed over time and space” (p. 17-18). Particularly in terms of rhetorical activity,

we might argue that what moves here is cultural capital and knowledge, to be

repackaged by human agents. As Prior et

al point out, “It’s about attending to semiosis in whatever materials at

whatever point in the activity” (p. 23).

In each model discussed, action

theory argues a dynamic system, one that allows recurrence as well as

change. Although human actors tend to

repeat things that work, circumstances vary, allowing minor shifts to occur

even when a genre, for example, is redeployed.

What would drive larger changes to the network would be changes within

the ecology. As time passes and as each

element of the system evolves or renews itself—either as a result of what

happens within the activity system under discussion or as a result of other

activity systems in the society—the system will shift slightly in new

directions. If we use the first

generation activity theory as a model, we can imagine an interviewer and

interviewee coming together to produce an interview. The interview is published, and it inspires a

graduate student to apply the ideas to another object of study. By the time the study is published to

significant acclaim, more journals have shifted to online formats. When the graduate student has become a noted

scholar and is interviewed, the network has changed. The subjects are different people, the online

nature of the interview has changed the genre as a mediational means, and,

although here the object is largely the same as in the earlier interview, the

outcomes may well be different. What

remains stable is how things tend to work within activity systems. Human beings still do accomplish things using

mediating tools.

An Evaluation

It is no accident that activity

theories have been attractive to genre theorists. Spinuzzi’s 2003 study, of course, traced

genres through time, exploring in depth how they functioned within a moderately

stable activity system. The main goal

for Nowacek’s (2011) study was understanding transfer in student writing, but

she is concerned with questions of genre as well, arguing that genre can serve

as exigence for or obstacle to transfer.

In a 1997 article David Russell

surveyed studies that used CHAT as an approach for exploring genre and writing

in higher education or workplaces. Unfortunately,

I was only able to get my hands on the abstract, but it does demonstrate the

fact that activity theories have been productive for genre researchers. Within activity theory, as already noted,

genres are mediational tools or instruments.

In this pivotal position, it is easy to track the importance of the

genre within the system, as indeed Spinuzzi does. Even though my own discussion here has only

proposed how the theory might work rather than actually applying it to specific

texts, it is easy to see how it could work.

If I were in fact to apply the framework to actual examples of academic

interviews, I would use Engeström or Spinuzzi’s model because these

versions of CHAT capture more of the ecological framework. On the other hand, the AT model has the

advantage of focus and simplicity. I

might want to reflect the generational development by making that the core of

my analysis. I would not use the version

proposed by Prior et al. For one thing,

I struggle with what I see as the incompatibility of terms. Things are not

quite “flattened,” as Latour (2005) tries to do, and yet there are not levels

either. Process elements are mixed with

spatial elements. Furthermore, some

elements can be conflated or exchanged: Socialization

arguably occurs through activity, ecology is the spatialization of socialization and activity, distribution is

a type of activity, and so are production and reception.

One final thing that I found

interesting about activity theory in general is that in a sense both AT and

CHAT are future oriented. It is true

that CHAT refers to cultural-historical

activity theory, but the system is not examined in terms of how it operated

through history. Rather the system is an

artifact of historical processes, an idea that is captured by the laminated

chronotopes of Prior et al’s version. In

other words, instead of focusing on what has happened historically, the

analysis is focused on the deployment of the activity system to reach not yet

realized goals. This is neither a

strength nor a weakness, but it is, nevertheless, an interesting feature of AT

and CHAT.

References

Arnold, W.

(2012). The secret subject: Michel Foucault,

Death and the Labyrinth, and the interview as genre.

Criticism, 54(4),

567-581.

Bourdieu, P.,

& Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An

invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bury, S. and

Scott, H. (2000). The artist speaks: The interview as documentation. Art Libraries Journal, 25(1), pp. 4-9.

Chakraborty, M.

N. (2010). Everybody’s Afraid of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Reading interviews

with the public intellectual and postcolonial critic. Signs: Journal of

Women in Culture and Society, 35(3), 621-645.

Eldred, M., &

Bazerman, C. (1995). "Writing Is Motivated Participation": An interview

with Charles Bazerman.

Writing on

the Edge, 6(2), 7–20. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43156966

Engeström, Y.

(1987). Learning by expanding: An

activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki:

Orienta-Konsultit Oy.

Giddens, A.,

& Pierson, C. (1998). Conversations

with Anthony Giddens: Making sense of modernity. Stanford, Calif: Stanford

University Press.

Latour, B.

(2005). Reassembling the social: An

introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nowacek, R. S.

(2011). Agents of integration:

Understanding transfer as a rhetorical act. Carbondale: Southern Illinois

University Press.

Prior, P., & Shipka, J. (2003).

Chronotopic lamination: Tracing the contours of literate activity. In C.

Bazerman & D.d Russell (Eds.),

Writing selves, writing societies:

Research from activity perspectives (pp.180-238). Fort Collins: The

WAC Clearinghouse and

Mind, Culture, and Activity. Retrieved from

http://wac.colostate.edu/books/selves_societies/prior/

Prior, P.,

Solberg, J., Berry, P., Bellwoar, H., Chewning, B., Lunsford, K.J., . . .

Walker, J.R. (2007). Re-situating and re-mediating the canons: A

Cultural-Historical remapping of rhetorical activity.

Kairos, 11(3).

Retrieved from

http://technorhetoric.net/11.3/binder.html?topoi/prior-et-al/index.html

Russell, D.R.

(1995). Activity theory and its

implications for writing instruction. In

J. Petraglia (Ed.), Reconceiving writing,

rethinking writing instruction, (51-78). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Russell,

D.R. (1997). Writing and genre in higher education and workplaces: A review of

studies that use cultural--historical activity theory. Mind, Culture,

and Activity, 4(4), 224-237.

Spinuzzi, C.

(2003). Tracing genres through

organizations: A sociocultural approach to information design. Cambridge,

Mass: MIT Press.

Tachino, T.

(2012). Theorizing uptake and knowledge mobilization: a case for intermediary

genre. Written Communication, 29(4), 455-476.

Van Oers, B.

(2010). Learning and learning theory from a cultural-historical point of

view. In B. Van Oers, W. Wardekker, E. Elbers, & R. Van Der Veer (Eds.), The transformation of learning: Advances in

cultural-historical activity theory (pp. 3-12). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Yamagata-Lynch,

L. C. (2010). Activity Systems Analysis Methods: Understanding Complex

Learning Environments. Berlin: Springer US.